In the wake of news that Apple plans to oppose a federal court order to assist the Justice Department in decrypting data stored on an iPhone belonging to one of the San Bernardino attackers, a broader conversation about encryption, privacy, and law enforcement has begun.

In theory, Apple could comply with the court order to create a version of iOS that would increase the likelihood of the FBI decrypting the phone’s data. But for Apple, this may open an ethical can of worms and potentially set a dangerous precedent for future criminal cases.

This case could ultimately sway both public and political opinions on government-mandated backdoors in mobile and computer operating systems.

The Facts

iPhones with iOS 8.0 or greater encrypt user data with an encryption key based on that particular iPhone’s embedded hardware-based key and the user’s PIN (or passcode). Without the PIN or passcode, it is impossible—even for the likes of Apple—to decrypt emails, messages, and photos stored on the iPhone. Everything is kept under the lock and key of encryption.

The FBI therefore needs to know the PIN or passcode to access the data. To guess the PIN or passcode, a brute-force attack is necessary (i.e., someone [or a computer program] repeatedly enters every passcode starting at 0000 through 9999 until the correct one is discovered).

To prevent brute-force attacks, the iOS operating system introduces two main security controls:

- It is possible to configure an iPhone to delete all encryption keys after 10 unsuccessful attempts at entering a PIN, thereby rendering the data inaccessible.

- iOS introduces incremental delays between unsuccessful PIN entries (assuming that the data isn’t rendered inaccessible after 10 incorrect PIN entries.)

The delays gradually ramp up so that for the first few times after entering a PIN, there is no delay between attempts. The more unsuccessful attempts, the greater the delay. The delay can range anywhere from several seconds to an hour.

This means that it could take over 400 days to guess a four-digit PIN. A six-digit PIN could take over 100 years. An eight-digit PIN? That could take over 11,000 years. The FBI may be trying to break into that iPhone well into the next Ice Age.

The FBI’s Version of iOS

Here’s where things get interesting. The incremental delays and data-wipe-after-10-attempts are strictly enforced by iOS—and Apple can program iOS to do almost anything, which means that Apple could create a version of iOS without those security controls. And that’s exactly what the FBI has requested in the court order, which demands from Apple a version of iOS that:

- Has no incremental delays between passcode entry attempts

- Has no automatic data-wiping feature

- Provides a way for the FBI to enter PINs in rapid succession until it finds the correct one

This iOS would be loaded on to the suspect’s device and used to recover the password. The FBI is not asking Apple to backdoor the encryption algorithms on all devices.

The success of this technique would depend upon the strength of the suspect’s PIN or passcode. On the back of an envelope, and assuming 100ms per PIN entry attempt, a four-digit PIN can be cracked very quickly – a matter of minutes in most cases. A six-digit PIN may take a day or so, and an eight-character alphanumeric password could take over half-a-million years to identify.

Open-source equivalents of the FBI’s request have actually been available for several years; however, the techniques only work against the iPhone 4 and older generations. The device in the San Bernardino case is an iPhone 5C.

These open-source tools work by exploiting weaknesses in the iPhone’s “bootrom.” The bootrom is a small piece of code that verifies that the phone’s software is digitally signed by Apple. The FBI cannot duplicate this signature and therefore cannot load its software on to the phone; similar to how an app developer must go through an approval process for the Apple App Store, the FBI needs Apple to digitally sign any modified version of iOS.

Bootrom exploits provide a method for bypassing this requirement; however, bootrom exploits are extremely difficult to develop. In fact, none have been discovered since 2010 (i.e., limera1n, SHAtter). This leaves the FBI with only one option to run customized attack code on the suspect’s device: coerce Apple into doing so on the FBI’s behalf.

Setting a Precedent

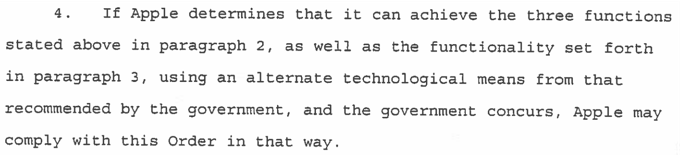

The FBI’s request isn’t exactly the most efficient. However, allowance is made for this in the court order:

In other words, the iOS operating system could automatically brute-force the PIN for the FBI. This technique could be used against any locked iPhone in the future, provided that the government can coerce Apple into signing the firmware with a secret key. This technique could be used to rapidly discover PINs and access encrypted iPhone data, providing that the targeted device’s PIN is sufficiently weak.

If we examine Apple’s response, it subtly hints at (without explicitly mentioning) this scenario. It seems that this is one reason Apple is refusing to comply with the FBI’s request.

Consider Apple’s language here:

Some would argue that building a backdoor for just one iPhone is a simple, clean-cut solution. But it ignores both the basics of digital security and the significance of what the government is demanding in this case.

In today’s digital world, the “key” to an encrypted system is a piece of information that unlocks the data, and it is only as secure as the protections around it. Once the information is known, or a way to bypass the code is revealed, the encryption can be defeated by anyone with that knowledge.

The government suggests this tool could only be used once, on one phone. But that’s simply not true. Once created, the technique could be used over and over again, on any number of devices. In the physical world, it would be the equivalent of a master key, capable of opening hundreds of millions of locks — from restaurants and banks to stores and homes. No reasonable person would find that acceptable.

The important distinction is the difference between the technique and the tool. Apple could create this attack tool to target the specific iPhone in question; however, the technique could be reused against any number of devices.

It looks like Apple fears that this could open the floodgates and set a precedent for modified versions of iOS to be created at the government’s behest. From Apple’s perspective, the FBI’s request is the tip of the iceberg. If the government can coerce Apple to write this backdoor, it can coerce Apple to write others, too. A few years in the future, Apple could be expected to deploy iOS updates over the air (“OTA”) to targeted individuals to steal their PINs, read all of their data, monitor their location, listen remotely to conversations, etc.

A Matter of Trust

Furthermore, it would be plausible that the government could force Apple into implementing weaker encryption standards in future versions of iOS for wider dissemination. FBI Director James Comey supports legislation that would outlaw strong encryption. This case is a small piece of a more intensive campaign by certain lawmakers to prevent products produced by companies like Apple and Google from containing strong encryption by default. This court order serves as a litmus test for furthering these kinds of measures.

A government-mandated “backdoor” in iOS would not help Apple’s reputation or bottom line, something that the Justice Department itself even acknowledged. Doing so would simply erode national and international trust in Apple's much-beloved products.

Apple is trying to prevent this scenario from manifesting into reality and that’s why it is challenging the court order. It’ll be interesting to see how this all plays out.

Joe DeMesy recently appeared on NPR to discuss this issue. We also wrote a follow-up to this original blog post following news that the iPhone was successfully decrypted by the FBI.

Subscribe to our blog

Be first to learn about latest tools, advisories, and findings.

Thank You! You have been subscribed.